By Ferrell Foster

My post the other day about The Silos brought to my attention a 2014 Waco Tribune-Herald story by J.B. Smith about those now famous silos. (Thank you, Ashley Bean Thornton.)

It seems that seven years ago this month there was some real uncertainty about the silos’ paint job, or lack of one. The Waco Downtown Development Corp. had originally given the go ahead for the Chip and Joanna Gaines project but with the understanding that the silos would be painted.

That rebuke of rust went to the Tax Increment Financing Zone board in October 2014. Chip (may I be so familiar) was not giving up on his rust. He told the board the silos “are impeccable and fashionable and interesting as they are,” the Trib reported.

The TIF board punted the aesthetic question back to the DDC, which led to a tour of the site guided by Waco’s First Couple (that being the Gaineses). DDC Chair Willard Still was skeptical going in. An hour later, he was convinced.

“We believe their plan will be a substantial improvement that the community will embrace,” the Trib reported Still saying. “They have a very sensible plan, and we embraced it.

“I have to give credit to Joanna Gaines. She has good taste, and that’s a proven product.”

Truer words have not been said. If Joanna walked into my home and said, “Ferrell, your favorite reading chair has got to go,” I would hesitate big time. She might reply, “I know you love that chair, but what if we got you a new chair that is better for your back, is loved by readers everywhere, and will make your study look like the most wonderful place in the world.” I would buckle quickly; it would be Joanna talking.

There are some people in town who are not big fans of the downtown boom fueled by Magnolia, but I’m not one of them. Not all development is good, but this one, I think, has been good for Waco.

We might wonder what would have happened if a paint job had been required and the Gaineses had pulled out the paint sprayers or hired professionals. We will never know, but I’m sticking with Joanne when it comes to good taste. She is the one-woman show (sorry Chip) that almost single-handedled revived the popularity of shiplap.

I’m thankful for the Gaineses and The Silos this Thanksgiving season. Just imagine this: What if they had done their thing in Austin or Temple or Hillsboro? We would be so jealous, and jealousy is not good for the soul. So may we all have a very Magnolia Thanksgiving — full of good taste all around, and I’m not just talking about style.

Ferrell Foster is senior specialist for care and communication with Prosper Waco.

The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email Ferrell Foster.

From the City of Waco Public Information Office

The Texas Historical Commission presented a THC Preservation Award of Merit to the First Street Cemetery Memorial Advisory Committee during the City of Waco Council Meeting Tuesday, Aug. 3.

The First Street Cemetery committee members Annette Jones (retired, City of Waco assistant city attorney), Nesta Anderson (archaeologist, principal investigator), and Melanie Nichols (archaeologist) were granted the Award of Merit for their significant contributions in historic preservation and public outreach through documentation of the First Street Cemetery project. Formal presentation of the award was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The First Street Cemetery, the oldest public cemetery in Waco, is south of the Brazos River and east of Interstate 35. After the 1960s construction of I-35, the City developed plans for a Texas Ranger Museum and campground, and a court order was issued in 1968 to disinter human remains within the proposed construction space to another portion of the cemetery.

However, in 2007, during construction of the Texas Ranger Company Headquarters building, it was discovered that human remains were still located in the area covered by the 1968 court order. As a result, the City, the National Park Service, THC, and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation executed a Memorandum of Agreement for the mitigation of adverse impacts to historical property and to remove the land use restrictions.

The Committee, consisting of sixteen community members, served between 2013 and 2018; it was formed and tasked with making recommendations to the City Council on the reburial of the remains, appropriate memorial services, plaques, and memorials to be erected at First Street and the reburial site. The Committee carefully took into consideration the community’s input and consistently provided thoughtful feedback for the many decisions to be made regarding reburials.

The THC and the City of Waco recognize the commitment of the Committee and these additional individuals to ensure a positive outcome for the impacts at First Street Cemetery and commend the example they provide for future cemetery projects.

The THC’s Award of Merit recognizes the efforts and/or contributions of an individual or organization involved in preserving Texas’ cultural and historical resources. This award recognizes the efforts and/or contributions of an individual or organization involved in preserving Texas’ cultural and historical resources.

The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email Ferrell Foster at [email protected].

By Terri Jo Ryan

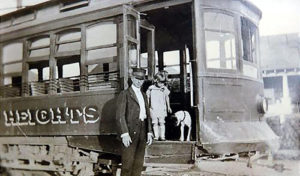

Waco was a city on the move at the turn of the twentieth century, and its run into modernity was aided by the advent of the interurban electric railway.

Although Waco had other forms of mass transit since the days of the stagecoach, with first mule-hauled and then electrically-powered streetcars, it was the Texas Electric Railway that ultimately inherited the early rights-of-way to do business in the city, though several transit firms vied for traffic in its early days.

Although Waco had other forms of mass transit since the days of the stagecoach, with first mule-hauled and then electrically-powered streetcars, it was the Texas Electric Railway that ultimately inherited the early rights-of-way to do business in the city, though several transit firms vied for traffic in its early days.

Citizen’s Railway Company, formed in 1877, used eighteen mule-drawn cars, and ten electric ones after 1891, to get commuters and shoppers where they needed to go until 1912. Southern Traction Company succeeded it, reconstructing tracks and adding extensions. Additionally, a streetcar company named Huaco Heights leased equipment from Citizen’s Railway Company and operated from 1913 to 1918, servicing the Huaco Heights real estate development.

It took John Frank Strickland, a man of vision and drive, to pull together the diverse elements to craft an efficient system. Strickland traveled to Texas by wagon train in 1878 from his native Alabama. He later went on to create the largest interurban rail system in the Southwest, with more than two hundred miles of track connecting commercial and cultural centers throughout the state.

Working his way up through plowing, cotton ginning, and then the grocery trade, Strickland became involved in electric power generation in Waxahachie in 1892. He later served as president of companies such as Texas Power & Light and Dallas Power & Light, positions he held until his death. Strickland and partners saw construction of interurban railroads as a complementary function of their power companies, and in 1908, a Strickland company began interurban service from Dallas to Sherman.

By 1911, Texas Traction operated seventy-seven miles of track from Dallas and Denison as well as local lines in Sherman, Denison, and McKinney. In 1912, interurban transportation from Dallas to Waxahachie began. The company extended the line to Waco in October of 1913, and absorbed streetcar lines in Waxahachie and Waco.

On New Year’s Day in 1917, Strickland merged Southern Traction Company and Texas Traction Company to create the Texas Electric Railway Company. The rail also served as the right-of-way for the electric power lines. Area drugstores and hotel lobbies sold tickets, offering different rates for children, clergy, and “excursion” groups. As ridership soared and business boomed, Strickland also won a postal contract to transport US mail, and employed a clerk to sort the letters and packages along the way.

The system’s usage peaked around 1920, when some 819,000 passengers rode the rails. The interurban’s decline began during the Great Depression, and the line started taking freight to make up for the loss of passenger revenue. Business rallied again during World War II, when gasoline shortages and rationing of rubber made rail travel more attractive than driving.

But after the war, the lure of private-car ownership and the development of better roads led to the system’s decline. The streetcar operations of Texas Electric Railway were sold to Waco Transit Company in 1946. As part of that sale, the streetcar continued to run from downtown to East Waco along the Texas Electric’s city track. But streetcar service ended when Texas Electric Railway ceased operations on December 31, 1948. Commuter service lasted for another year by the Texas Electric Bus System before being entirely phased out. Within days of the company’s closure, workers began pulling up tracks and taking down copper wire to sell off the assets and liquidate.

Remnants of the interurban railway remain visible in downtown Waco today. Pylons which once supported the interurban bridge as it spanned the Brazos River (noted on the Waco History map) offer a constant reminder of the interurban’s legacy of providing citizens with a convenient and economical means of transportation both throughout the city and the state.

Cite this Page

Terri Jo Ryan, “Interurban Railway,” Waco History, accessed January 4, 2018, http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/117.

This post was first published in “Waco History.” Waco History is a mobile app and web platform that places the past at your fingertips! It incorporates maps, text, images, video, and oral histories to provide individuals and groups a dynamic and place-based tool to navigate the diverse and rich history of Waco and McLennan County. It is brought to you by the Institute for Oral History and Texas Collection at Baylor University.

This post was first published in “Waco History.” Waco History is a mobile app and web platform that places the past at your fingertips! It incorporates maps, text, images, video, and oral histories to provide individuals and groups a dynamic and place-based tool to navigate the diverse and rich history of Waco and McLennan County. It is brought to you by the Institute for Oral History and Texas Collection at Baylor University.

The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email [email protected] for more information.

For many years, Sanger Avenue Elementary School stood as the most familiar landmark of the Sanger Heights neighborhood. Located in the “Silk Stocking District,” Sanger Avenue Elementary acquired a reputation as one of the premier educational institutions in the city.

A 1903 bond election resulted in the construction of three nearly identical schools. Sanger Avenue School, designed by renowned Waco architect Milton W. Scott, long outlasted its counterparts Bell’s Hill and Brook Avenue Elementary Schools. The two-storied building featured unique architecture and elaborate design, including ornate arches, a rotunda, an upstairs auditorium, and a high roof crowned by a cupola. The building’s heavily Romanesque style included arched windows and doors framed by limestone. Prominently featured turrets stood at the front of the original school building but were removed in a 1930 renovation.

A 1903 bond election resulted in the construction of three nearly identical schools. Sanger Avenue School, designed by renowned Waco architect Milton W. Scott, long outlasted its counterparts Bell’s Hill and Brook Avenue Elementary Schools. The two-storied building featured unique architecture and elaborate design, including ornate arches, a rotunda, an upstairs auditorium, and a high roof crowned by a cupola. The building’s heavily Romanesque style included arched windows and doors framed by limestone. Prominently featured turrets stood at the front of the original school building but were removed in a 1930 renovation.

Sanger Avenue School opened in 1904 with John H. Richardson as its first principal. Former students and teachers generally agree that the most influential figure in the history of Sanger Avenue was likely Nina Glass, the school’s second principal. Glass encouraged parents and students to take an active role in education, establishing a mimeographed newsletter for parents called the Ginger Jar and inviting students to save coupons to buy pictures for the school. She published a nationally used arithmetic textbook and frequently attended educational conferences. Well liked by both staff and students, Glass was often seen at the school’s annual May Fete festival, brightly garbed and leading students in a parade around the Maypole.

Sanger Avenue School opened in 1904 with John H. Richardson as its first principal. Former students and teachers generally agree that the most influential figure in the history of Sanger Avenue was likely Nina Glass, the school’s second principal. Glass encouraged parents and students to take an active role in education, establishing a mimeographed newsletter for parents called the Ginger Jar and inviting students to save coupons to buy pictures for the school. She published a nationally used arithmetic textbook and frequently attended educational conferences. Well liked by both staff and students, Glass was often seen at the school’s annual May Fete festival, brightly garbed and leading students in a parade around the Maypole.

Glass’s enthusiasm reflected the general atmosphere at Sanger Avenue Elementary. Former students fondly remember dedicated teachers and classrooms ideally suited for learning. Large windows poured light into classrooms where each student’s cast-iron and wooden desk held an inkwell. A spacious and well-stocked library, established after Glass attended a Chicago educators’ conference, invited students to study and read.

The years following Glass’s retirement from Sanger Avenue brought great changes for the small elementary school. By the 1960s, over seven hundred students attended the school, and music classes and a choir were established. Yet the Waco Independent School District (WISD) announced plans for the school’s closure as a part of a busing plan to meet a federal desegregation order. By the 1970s, African American students made up approximately half of the school’s population. Despite the efforts of many to keep the school open, classes ceased at Sanger Avenue in 1974.

Although a portion of the school briefly housed a Head Start program, much of the building soon suffered from years of disuse. Disappointed at seeing such an important piece of Waco’s history sit vacant, Waco attorneys LaNelle and John McNamara purchased the school for $80,000 from WISD. The couple renovated the building, installing a new roof, boarding up broken windows, and removing asbestos. Yet despite their hopes of repurposing the building, perhaps as a charter school, the plans never came through. Another blow was dealt to the historic building when arsonists set fire to it in 2008.

The city of Waco deemed the building unsafe, and in 2010 bulldozers tore the remnants of the structure down, leaving only the entrance archway standing. The school’s former location has been featured in the Waco Trib recently as a possible location for an indoor soccer field.

Cite this Page:

Karen Green and Cheryl Wiggington, “Sanger Avenue Elementary School,” Waco History, accessed July 19, 2017, http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/112.

Waco History is a mobile app and web platform that places the past at your fingertips! It incorporates maps, text, images, video, and oral histories to provide individuals and groups a dynamic and place-based tool to navigate the diverse and rich history of Waco and McLennan County. It is brought to you by the Institute for Oral History and Texas Collection at Baylor University. This post: Prisca Bird, “Lovers’ Leap,” Waco History, accessed June 21, 2017, http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/38.

Waco History is a mobile app and web platform that places the past at your fingertips! It incorporates maps, text, images, video, and oral histories to provide individuals and groups a dynamic and place-based tool to navigate the diverse and rich history of Waco and McLennan County. It is brought to you by the Institute for Oral History and Texas Collection at Baylor University. This post: Prisca Bird, “Lovers’ Leap,” Waco History, accessed June 21, 2017, http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/38.

The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email [email protected] for more information.

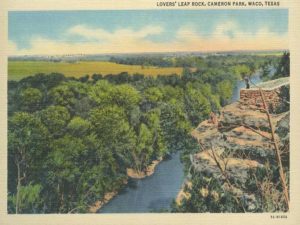

A picturesque limestone bluff situated high above the Bosque River, Lovers’ Leap is as dangerous as it is beautiful.

On June 28, 1917, the Cameron family purchased a tract of sixty acres featuring the cliff area known as Lovers’ Leap. Though it had been the site of many picnics and romantic excursions, Lovers’ Leap had yet to receive formal designation as a park site. The Camerons originally leased the land to the federal government with the understanding that when Camp MacArthur troops no longer needed it as a recreation space, it would be added to Cameron Park. On September 3, 1920, the Cameron family acquired the remaining 191 acres between Cameron Park and Lover’s Leap, thereby ensuring the bluff would remain a central attraction in one of Texas’ largest municipal parks.

On June 28, 1917, the Cameron family purchased a tract of sixty acres featuring the cliff area known as Lovers’ Leap. Though it had been the site of many picnics and romantic excursions, Lovers’ Leap had yet to receive formal designation as a park site. The Camerons originally leased the land to the federal government with the understanding that when Camp MacArthur troops no longer needed it as a recreation space, it would be added to Cameron Park. On September 3, 1920, the Cameron family acquired the remaining 191 acres between Cameron Park and Lover’s Leap, thereby ensuring the bluff would remain a central attraction in one of Texas’ largest municipal parks.

Associated with the cliff is a folktale involving two star-crossed Native American lovers. As recounted by Decca Lamar West in her popular 1912 booklet The Legend of Lovers’ Leap, Waco Indian maiden Wah-Wah-Tee secretly accepted a marriage proposal from a handsome Apache brave despite the enmity between their tribes. The two hoped to elope but were thwarted in their effort to run away quietly at night by Wah-Wah-Tee’s father and brothers who objected to the union. Cornered at the edge of a steep cliff above the Bosque, Wah-Wah-Tee and her brave chose to embrace one another and leap into the swollen river below rather than face a lifetime apart. The bodies of the two, still holding tightly onto one another, found a final resting place on the banks of the river close to the site of their first meeting. While stirring, no historical basis exists for the tale. It is most likely a byproduct of late-Victorian romanticism and efforts to promote one of Waco’s natural wonders to outsiders.

Since its establishment as an official outlook, Lovers’ Leap has presented a genuine safety concern. In an effort to safeguard the public from the cliff’s edge while not obstructing the splendid view of the surrounding countryside, park authorities constructed short stone walls. However, select visitors in pursuit of a better vantage point sometimes ignored these barriers, leading to personal injury or in certain cases death. In order to improve safety at the outlook and spruce up its appearance in time for the park’s centennial, the city of Waco constructed new fences in 2009 and removed foliage on the cliff face to enhance the view from the designated overlook plaza.

For close to one hundred years, Wacoans and tourists alike have been drawn to the dangerous beauty of Lovers’ Leap.

Waco History is a mobile app and web platform that places the past at your fingertips! It incorporates maps, text, images, video, and oral histories to provide individuals and groups a dynamic and place-based tool to navigate the diverse and rich history of Waco and McLennan County. It is brought to you by the Institute for Oral History and Texas Collection at Baylor University. This post: Prisca Bird, “Lovers’ Leap,” Waco History, accessed June 21, 2017, http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/38.

Waco History is a mobile app and web platform that places the past at your fingertips! It incorporates maps, text, images, video, and oral histories to provide individuals and groups a dynamic and place-based tool to navigate the diverse and rich history of Waco and McLennan County. It is brought to you by the Institute for Oral History and Texas Collection at Baylor University. This post: Prisca Bird, “Lovers’ Leap,” Waco History, accessed June 21, 2017, http://www.wacohistory.org/items/show/38.

The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email [email protected] for more information.