(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

Rethinking Racism

By Baltazar Acevedo y Arispe, Jr.

And here we go again. Ferguson and its aftermath have sparked renewed interest, debate and introspection of how we Americans act against each other in a destructive manner.

The president is anguished and demonstrates his consternation by appointing another taskforce to solve the problems that are rooted beyond the grasp of Washington. Yes, $75 million will solve all ills. Local political leaders waver and walk the fence in distress, as they are afraid to address this most volatile issue. As a nation we again look at the aftermath of the Civil Rights Era and find that not much has really changed. The only change is that racism is now practiced in more subtle and sophisticated ways.

By every measure of social advancement, the poor have become poorer, the homeless remain without a home, and the illiterate have become more illiterate, the economic and politically disenfranchised remain so. Women continue to suffer neglect, not only in abusive relationships but also in their economic well being as they continue to earn at least 35 percent less than their male counterparts for the same labor. These are the seed that sow the roots that nurture racism and its exclusionary nature.

Racism, at its core, is about exclusion, pure and simple. It is about leaders who are afraid to come face-to-face with the shifting demographics and the fact that ethnic America is just over the horizon. As one who was involved in the Civil Rights Movement and worked with Cesar Chavez in our struggles to expand the rights of Chicano farm workers, I know racism. I see it daily; it has its own scent and its own taste and it can be touched as it meanders within communities, its school districts, civic organizations, its congregations and its institutions of higher education. It has become so pervasive that it permeates the actions of policy brokers who fail to see it or simply ignore it as they continue with their disenfranchisement of those at the lower rungs of the social ladder. I also see its aftermath in the homeless shelters, food banks, its community kitchens, centers for abused women and community based agencies that work daily to stem the tide of poverty and the sense of hopelessness of those that wander the streets searching for a lost future.

As Bob Dylan’s lyrics remind us, “you do not need a weatherman to tell which way the wind the blows.” The wind still blows with the essence of racism and once in a while the tip of the volcano explodes and the lava flows with the hatred and frustration as a response to oppression and threatens our comfort zone.

So what is it that I have learned about racism? I have learned that:

- It is not about hatred or purposeful malice.

- It is not about you, me and them hating others because of their skin color, ethnicity or gender.

- It is not about your willingness to destroy me or my will to do the same to you.

- It is about ignorance and misinformation by one group or an individual about another.

- It is about fear of those in “power” that those without control and influence will attempt to diminish the role of the power brokers.

- It is about an unwillingness to share the means to bring about change in a shared community.

- It is about a willingness to exclude those that are different, who speak differently, have a national origin that is seen as threatening, who have a different religious affiliation, and who have a sexual orientation that may be seen as abhorrent and who view the world through different lenses.

- It is about having a feeling that someone is a threat to whatever social status quo one has and wishes to keep.

- It is about a misguided perception that a self ordained or self-appointed cadre of leaders can “empower” the less fortunate.

- It is about an unwillingness to become informed about the “others.”

- It is about a failure to realize that when the boat sinks that we will all surely drown unless we all work to fix the leaks in the social infrastructure.

- It is about hubris and a belief by a select few that they know what is best for the rest of us.

- It is about not doing the right thing and subscribing to the principles of omission and commission to guide exclusionary public policies and their corresponding practices of neglect.

- All politics is local and so is racism. If we cannot resolve our differences in the compressed geographic space that we share then how can we propose to affect change on a regional, national or global scale?

So the question is this: Is your or my community living near the volcano that is spewing the fire and lava of oppression, frustration or isolation that will one day erupt as it did in Ferguson? Most importantly, what will be the match that lights the next powder keg? The challenge is for us to go beyond dialogue and to assertively take on measures to be more inclusive and to commit to a system of shared accountability for our development as communities that can work together toward to becoming vested stakeholders in a common future. The option of not doing so is rather evident; it comes full-blown into our living rooms on CNN and on our smart phones. Wanton destruction only serves to pollinate the soil for the next harvest of hatred and racism.

Baltazar Acevedo y Arispe, Jr., Ph.D. is a Chicano activist who spent 45 years at all levels of education. He left the University of Texas System in 2012 as a tenured professor of leadership and research. He resides in New Mexico and Waco, Texas.

Baltazar Acevedo y Arispe, Jr., Ph.D. is a Chicano activist who spent 45 years at all levels of education. He left the University of Texas System in 2012 as a tenured professor of leadership and research. He resides in New Mexico and Waco, Texas.

(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

A Movement towards Color-Sightedness

My name is Amber Jekot and I’m a recovering racist. I say recovering because I confess that I have not arrived. I say recovering because I’m working towards becoming more conscious of an experience that is not, nor will ever be my own. I both admit and commit to the ongoing journey towards race consciousness, a journey that, like Lucas Land and Kelsey Miller before rightly articulated, begins with submitting myself to the position of a student. I am indebted to the friends, professors, and community members of color who have been patient enough to teach me, a patience that must have, at times, been painful.

I know something of being misunderstood, just as everyone does. Being misunderstood, misrepresented, victim to false assumptions. Yes, these are experiences common to us all, and I don’t know about you, but I can’t stand being misrepresented. I am careful to articulate my words so that my intentions are communicated in such a way that others can understand. I present myself professionally because, let’s be honest, my size isn’t proportional to my age. I choose prudently those with whom I share my pain because there is nothing worse than baring your heart to someone who doesn’t validate your experience. I can remember the emotions evoked during such times, blood rushing to my face, exasperation rising in my lungs, and the resulting inability to articulate a retort due to the magnitude of my frustration: “How can you discount something just because it was not your experience?”

Well, the things that bother us most about other people generally have their basis in what we lack within ourselves, a frustrating reality indeed. One of the lessons I have learned in my personal journey toward becoming more conscious of racism was the debunking of the colorblind myth, a lesson for which I have Dr. Sanders to thank.

Dr. Sanders, a black man whose height can only be described as tremendous, came to talk to a group of students, myself included, whose understanding of race was as small as our comparative statures. Dr. Sanders shared that while generally well-meaning, the following and often-used statement is offensive to him: “I don’t see you as a black man, I just see you as a man.” Upon first glance, perhaps this statement does seem innocent. It did for me. I scooted up in my chair with curiosity, and quizzically listened as Dr. Sanders continued: “That statement is a ridiculous as you saying to me, Alvin, I don’t see you as a tall man, I just see you as a man.” He paused, giving us the time to take in his height, and then he continued, “Are you all seriously going to tell me that you don’t see my height?”

He went on to explain that when people choose to not see color, it often feels like people are also choosing to not see the effects that racism has on people of color. There is something about largeness that people are comfortable with; there is something about blackness that causes us to pause. Our culture doesn’t claim mottos such as size-blindedness, but claims colorblindness, a reality that divulges a discomfort implicit in the mention of race.

He went on to explain that when people choose to not see color, it often feels like people are also choosing to not see the effects that racism has on people of color. There is something about largeness that people are comfortable with; there is something about blackness that causes us to pause. Our culture doesn’t claim mottos such as size-blindedness, but claims colorblindness, a reality that divulges a discomfort implicit in the mention of race.

In claiming colorblindness it often seems that we are neglecting to acknowledge the impact of color, neglecting to acknowledge realties such as these:

People of color are overrepresented in the US penal system for illicit drug use despite the fact that “Data on illicit drug use collected by the Health and Human Services Commission has consistently shown over time that whites, African Americans, and Latinos use drugs at roughly comparable rates” (Mauer & McCalmont, 2013, p. 6; Stevenson, 2014; Alexander, 2011).

According to the CDC, “The infant mortality rate among African Americans is 2.3 times that of non-Hispanic whites.” Additionally, African American infants are 4 times more likely than non-Hispanic white infants to die due to complications related to low birthweight.”

Perhaps such a reality feels too heavy to hold. Perhaps colorblindness is our way of saying “this can’t be so”— well meaning but vision-impaired.

When I read books like Just Mercy or the New Jim Crow, books that detail breaches of justice in the US penal system, I find myself having to put these books down because the reality feels like “too much” for the present moment. When I find myself overwhelmed by stories my friends of color share with me about implicit or explicit racism, I have to “escape” from my thoughts because I can’t imagine that anyone could treat my friends with such disdain. The pain, which feels overwhelming for me, is something that I, as a white, middleclass woman, can choose to pick up and put down, to look at or keep my eyes closed. That is privilege.

Perhaps those who are the most brave are the men and women of color who have boldly continued to share their experiences despite my own and others invalidating responses. To you, the brave, please keep speaking. The journey of the color-blind and color-sighted are indebted to your vulnerability. To those who are on the journey, however far along you are, or if perhaps you’re ready to begin the journey: let’s commit together. Instead of falling prey to white guilt, let us instead capitalize on this energy and direct it towards forward momentum. Let us speak alongside our brothers and sisters of color because this burden becomes lighter when we see and speak together. Solidarity, a good friend recently shared, means that no one or no group should have to stand alone.

Perhaps those who are the most brave are the men and women of color who have boldly continued to share their experiences despite my own and others invalidating responses. To you, the brave, please keep speaking. The journey of the color-blind and color-sighted are indebted to your vulnerability. To those who are on the journey, however far along you are, or if perhaps you’re ready to begin the journey: let’s commit together. Instead of falling prey to white guilt, let us instead capitalize on this energy and direct it towards forward momentum. Let us speak alongside our brothers and sisters of color because this burden becomes lighter when we see and speak together. Solidarity, a good friend recently shared, means that no one or no group should have to stand alone.

Today’s Act Locally Waco blog post is by Amber Jekot. Amber is an 8-year Waco resident who works as a graduate assistant at the Texas Hunger Initiative. She is finishing a masters of social work at Baylor University and a masters of divinity at Truett Seminary. She is passionate about the intersection between food, justice, and community and has been known to take trains without knowing her destination. You may contact her via email at [email protected].

Today’s Act Locally Waco blog post is by Amber Jekot. Amber is an 8-year Waco resident who works as a graduate assistant at the Texas Hunger Initiative. She is finishing a masters of social work at Baylor University and a masters of divinity at Truett Seminary. She is passionate about the intersection between food, justice, and community and has been known to take trains without knowing her destination. You may contact her via email at [email protected].

Sources:

Alexander, M. (2011). The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness (revised ed., p. 1). New York: New Press.

Fact Sheet: Health Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/reports/CHDIR11/FactSheets/Insurance.pdf

Mauer, M., & McCalmont, V. (2013). A Lifetime of Punishment: The Impact of the Felony Drug Ban on Welfare Benefits. Retrieved from http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publicationscc_A%20Lifetime%20Punishment.pdf

Stevenson, B. (2014). Just mercy: a story of justice and redemption (p. 1). New York: Spiegel & Grau.

(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

by Ruben Salazar

I’ve never been shot at by a cop or chased by sheets-wearing men, but I have been at the receiving end of power-toting bigots. In many ways, I’m also surrounded by an important aspect of racism—white power (known by some as just “white privilege”). People of color will be on to something positive in our city when we can find ways to dilute dominant white power structures. In my opinion, one of the best ways of doing this is by fighting for diversity (not just tokenism) wherever there are seats at the tables of power.

My friend Sonya said something interesting to me one day. She commented about how some of us go through a ‘get back at whitey’ phase. We had been chatting about the lack of racial diversity around Waco. Sonya is a black woman. I felt an immediate bond with her because we shared the same frustration with white power and privilege. By the way, neither Sonya, nor I, nor others we associate want to get back at anyone. To ‘get back at whitey’, used in the way it rolled off Sonya’s tongue, is the desire to change the white power system. (Try reading Howard Zinn’s, A People’s History of the United States, for a benign introduction to white oppression.)

Personal experiences also fuel my desire for change.

For example, I’ve been frisked a few times—for no reason—by white cops for committing minor traffic violations. A white sheriff once flipped me off for no reason when I went to visit a friend at the county jail—I was just 15. And then there was the white highway patrol officer who pulled me over for doing 62 mph on a 60 mph zone. He frisked me, then told me to get into his patrol car’s passenger seat. I asked him if this was protocol. To this, he answered with his heavy twang, “Boy, I do what I want!”

Through the years, I’ve heard white supervisors make comments about how they hate hearing Spanish spoken at work. A white manager once told me that black universities are a form of reverse racism. I’ve been told by white company leadership that Affirmative Action policies only invite unqualified black and Latino personnel who can’t do the work as well as “someone who got the job because they were properly qualified” (i.e., the white person). Two white people, just this past year, boasted to me about their racist actions: one used to shoot his BB gun at blacks walking down the street and the other used to put snakes in the jeeps of black soldiers when he was in the military. Would they admit the same in the face of a black person?

Encounters with racism and white power aren’t always so stark and in your face. For starters, there is a long list of examples of institutionalized racism. Also, there are many white people who exert white power without knowing that they’re doing so. For example, some churches and religious charitable organizations enjoy imposing their power onto non-whites and poorer whites. I used to live in an area in North Waco that is apparently ripe for “community service projects.” I’ve grown accustomed to seeing young white volunteers mow yards and clean up blighted areas for tenants who must be too poor to mow and clean. I know because my yard got mowed once, without my consent, while I was away from the house! That was the day I learned I was poor.

And get this: once, while my wife and I were cleaning our yard, a young white couple walking by stopped and asked us if we were providing “service to the homeowners”! Wow! Who knew people could take care of their own yards?

Can you think what would happen if I—a brown-skinned Mexican—moved to a white upper-class part of town, set up my charity, and began to impose changes on the neighborhood that I thought were needed?

Able-bodied people of color shoot themselves in the foot when they accept having their yards mowed or their houses painted. This acceptance just perpetuates the idea that we need their help. “Never do for someone what they can do for themselves”. Now there’s a motto that, if upheld by everyone, would tear down a large chunk of the white power structure lurking in our communities.

Our society will be a better place when blacks, Latinos, poor whites, and others perceived as needy, do for ourselves, instead of relying on the handouts and freebies from entities designed by whites with power — some of whom turn around and complain about poor peoples’ demands for entitlements. This is an argument for grassroots community organizing amongst minorities, but that’s another story.

It would also help if white (and other) insistent do-gooders could begin to view blacks, Latinos and poorer whites as having strengths and abilities, instead of having deficits and having to aspire to middle class values (e.g., the Ruby Payne framework). My suggestion is that they re-educate themselves and others with white power about how their charitable acts, funds and other support, in many ways, perpetuate the very problems they think they’re trying to eradicate.

People of color should continue the fights of our forefathers and mothers for racial equality. We should continue to demand racially diverse leadership (at all tables of power—community organizations, business, government, education, etc.) that mirrors the diversity of our communities so that we can begin to diminish the historical specter of white power and privilege.

Ruben P. Salazar is a native Wacoan who enjoys learning about history and culture. He is an artist and a do-it-yourselfer around the house. In the very near future he swears he’ll finally self-publish his long overdue book about a local dude people used to call the Maracas Kid. Gardening and being crafty are two things he loves to do with his lovely wife, Rachel.

Ruben P. Salazar is a native Wacoan who enjoys learning about history and culture. He is an artist and a do-it-yourselfer around the house. In the very near future he swears he’ll finally self-publish his long overdue book about a local dude people used to call the Maracas Kid. Gardening and being crafty are two things he loves to do with his lovely wife, Rachel.

(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

By Kelsey Miller

I want to recognize the great work Lucas did in his post in this series by echoing his confession: I am racist. We all are. I say this in a spirit of deep repentance, which is where any truthful conversation about race must begin. This beginning also protects us from the dangerous temptation to think that we will somehow transform our culture into a utopia where we will each transcend racism and become color-blind. Better instead to accept and find meaning in the challenge of the work of un-packing our own biases, conscious and subconscious. That is good and fruitful work that we might all dive into together for a lifetime.

I grew up outside Chicago in a very white, very privileged suburb. It was not until I moved to Texas that I first heard a blatantly racist comment, spoken by one white person to another. The naïve temptation in that moment was to believe that somehow, the more highly evolved North was devoid of racism, while the South is filled with it. With more exposure, I soon learned that racism is not a geographical problem or cultural problem; it’s a human problem. Still, in the last few years that I’ve lived in Texas, I am sobered by the number of times I can recall where I said nothing in reply to both explicitly and implicitly racist comments.

One tool that has helped me to analyze some of these comments and attitudes, and to continue questioning my own stereotypes and biases, is to read books and articles by African American authors who are critically engaging issues of race, power, and privilege in our culture. I am deep into Bryan Stevenson’s new book Just Mercy, and I believe his prophetic witness to the deep brokenness in our criminal justice system in the form of racial and socioeconomic disproportionality is changing me permanently.

Stevenson writes, “Today we have the highest rate of incarceration in the world. The prison population has increased from 300,000 people in the early 1970s to 2.3 million people today…One in every fifteen people born in the United States in 2001 is expected to go to jail or prison; one in every three black male babies born in this century is expected to be incarcerated.”

Stevenson goes on, “Some states permanently strip people with criminal convictions of the right to vote; as a result, in several Southern states disenfranchisement among African American men has reached levels unseen since before the Voting Rights Act of 1965.”

If you did not already know this, does it surprise you? I am shocked by the statistics and stories Stevenson shares in this book. Stories of systemized violence against people of color, of intentional legal misrepresentation of African American clients, of scores and scores of laws in our country that are less than 50 years dead that routinized and systemized the inferior status and treatment of people of color. I can own up to the fact that it is a privilege to be shocked, but I hope never to stop there. It is only when you and I use that shock to fuel us to keep reading, to keep listening, and to keep having the hard conversations that it becomes truly valuable.

Stevenson’s work has empowered me to engage more critically and respond more vocally to daily instances and examples of the dangerously disproportionate systems he unpacks. For white people, this means first confessing our own participation in racism, even if we think it only happens inside our own heads, and then resisting the urge to remain silent when other white people make openly or implicitly racist remarks. I used to think that it wasn’t worth risking a relationship or upsetting a temporary calm to call out wrong when I heard it. And I doubted my own strength, or that a few comments from me on the destructive nature of racism could be effective. How often do I tell myself that lie? That people can’t change or won’t understand, and it’s better for me to just be quiet?

Perhaps the more sobering question is this: is false harmony more valuable than the everyday pursuit of equality and justice?

A switch flipped when I realized that I can choose to either sell out people of color by refusing to openly condemn racism when I see it in action, or I can summon the courage to say something when it would be easier to be quiet. I’ll admit that this understanding of “bravery” is really lame and cheap in the wake of protestors who took to the streets of Selma, the bus boycotters who endured beatings and abuses, the unjustly tried and accused who faced all-white juries presented with zero evidence, followers of Dr. King and Malcolm X who were willing to give their all so that they might be heard, and so many more. Still, my voice is what I have, and speaking up is one thing I can do. So rather than be immobilized by the weight of my privilege and frustration, I can choose to say something. I can decide that false harmony is not more valuable than the everyday pursuit of equality and justice. I can risk the hurt feelings or shock of neighbors, colleagues, family, and friends when I tell them that comment they just made was NOT ok (and why).

And, since I started this post with a confession, I’ll end it with one: I am pretty terrible at being brave, most especially about a topic as challenging and uncomfortable as racism. But I’m trying, and I’m working on it, and I’m learning from people who are much braver and wiser than I am.

Will you join me? How can we be brave together today?

Kelsey Miller is a Child Hunger Outreach Specialist at Texas Hunger Initiative’s Waco Regional Office. She is passionate about more people gaining access to and education about healthy foods and our food system, and thinks the expertise of those experiencing hunger and poverty should always be our starting point. Kelsey lives with her husband and rambunctious puppy in Waco, and is also pursuing an MSW from Baylor part-time.

Kelsey Miller is a Child Hunger Outreach Specialist at Texas Hunger Initiative’s Waco Regional Office. She is passionate about more people gaining access to and education about healthy foods and our food system, and thinks the expertise of those experiencing hunger and poverty should always be our starting point. Kelsey lives with her husband and rambunctious puppy in Waco, and is also pursuing an MSW from Baylor part-time.

(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

A Bad Day – By Shamethia Webb

She was having a bad day.

And what exacerbated it was the fact that it wasn’t unusual.

She awoke on time (which meant early for her). Showered. Brushed her teeth. Scowled at herself in the mirror. And went to work.

All of her co-workers were talking about the black boy who was murdered while walking from a convenience store. They’d been talking about it for days. Talking about it and doing nothing. The same words again and again as if the incessant movement of their mouths negated a seventeen year old corpse.

She hated them.

During her break she washed and rewashed her hands in the restroom. She abhorred being in the ladies room for longer than a few minutes. It smelled like women. Which meant it smelled like pain and fatigue.

She wrenched a paper towel out of the dispenser and cast a frown at the vacant stalls that seemed to mock her loneliness.

She was tired.

She didn’t speak during staff meeting. Didn’t see the point in disturbing her tongue. They always smiled over her suggestions. Or tasted her words with their mouths before spitting them out. It infuriated her. Mostly it hollowed her. Cleaved into her like a perforated knife and emptied her out.

She’d spilled so much of herself over these hallways during her tenure here. Specks of herself all over the walls. Now a permanent grimace clung to her face like love.

The smell of coffee hung in the air. Stale. A room full of spit and disdain. She inhaled. Yes, disdain. She could smell it on them like second skin.

They were talking about him again. Her boss didn’t use the word murder. But defense. And mistake. And misunderstanding.

She hated him.

Her co-worker, the one with a frown for a smile, giggled at her boss’s comment that the black boy should have ducked the bullets.

I thought black boys were fast, he joked. A room full of laughter.

She died a little bit.

But not enough. She still had to clock out. And smile at the receptionist who always mispronounced her name. She still had to leave the building—and them, and them—with as much of herself intact as possible.

She stumbled to her car, trembling in her black woman fury.

She was tired.

In the checkout line at the supermarket, she watched as her few items moved lazily up the conveyor belt. The cashier chatted animatedly with the customer in front of her.

Don’t let this cashier cut her eyes at me, she thought to herself. Not today.

Don’t let her reach for my money with two fingers as if she’s afraid of skin contact. Don’t let her suddenly become mute and unresponsive to my presence, to my human being-ness. Don’t let her. Not today.

She realized with some panic that it wasn’t anger that fueled her thoughts but despair. She recognized that if the cashier did de-humanize her today she wouldn’t respond with fury but with resignation.

The passivity worried her.

I’m dying too fast, she thought.

She tensed as her items moved closer to the cashier, and she couldn’t help but notice that the murdered boy’s eyes stared back from every magazine in the aisle.

The repetition overwhelmed her. She shook.

Pieces of herself broke off. Landed dully on the laminate floor.

She tried to remember her breath. And forget her boss and the restroom stalls and the hundreds of cashiers who’d humiliated her and the tiptoeing gunman and the black corpse and the black corpses theblackcorpsestheblackcorpsestheblackcorpsetheblacktheblacktheblackblackblack

She tried to catch herself but her hands were already gone. Dead.

. . .

I hate soap operas.

A voice behind her.

She opened her eyes. When had she closed them?

A white man behind her scowled at a TV guide featuring frozen celebrities. He turned a full smile on her. The white of his teeth blinding for a moment.

Don’t you just hate soap operas?

She managed a nod.

She did hate them. This aisle was full of things she hated. This city. This world. Full of things she hated. Or perhaps just full of things (No. People, she amended. She liked being correct). Full of people who hated her.

I’d rather read the back of a cereal box than watch TV, the man said.

He picked up one of his boxes of cereal and waved it at her.

This isn’t food but entertainment.

She smiled. Not a full one (she was incapable of that at this point) but a slash of the mouth that surprised her with its suddenness.

. . .

And there was a pocket of time when he wasn’t who he was or had to be and she wasn’t who she was or had to be. They just were.

And there was a glimmer inside of her. Something not quite dead, that stirred.

The cashier was aloof but polite. And that was enough.

She walked to her car without the usual trembling.

The white man (No, man, she corrected) was parked beside her. They chatted as they loaded their items into their cars.

Well, he chatted. She managed to listen without the usual weariness and rage.

Perhaps she would sleep in tomorrow.

Yes.

Perhaps she would grow again.

And as she slid into her driver’s seat, a murmur of a smile across her face, the man waved a crumbled bill in her face and propositioned her for sex.

Shamethia Webb (on the right in the picture) is the Regional Director of the Texas Hunger Initiative Waco Regional Office. She grew up in Waco and spends her free time writing, dreaming, and trying to protect her reign as Connect Four Champion from her nephews. Hip hop music, sour candy, and Toni Morrison novels are a few of her favorite things.

Shamethia Webb (on the right in the picture) is the Regional Director of the Texas Hunger Initiative Waco Regional Office. She grew up in Waco and spends her free time writing, dreaming, and trying to protect her reign as Connect Four Champion from her nephews. Hip hop music, sour candy, and Toni Morrison novels are a few of her favorite things.

(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

I just want to say one thing. It’s very simple and I’m not supposed to say it. I am racist. Most of the time I don’t know I’m racist and I don’t mean to be racist, but I am. I wouldn’t know much about my own racism if it weren’t for friends of color leading me and teaching me. Friends like Pastor Delvin Atchison of Antioch Baptist Church in Waco. Like my friend Luis and like my friend DeShauna.

You see, White people, like myself, need our brothers and sisters of color to teach us about racism. We are blinded to so many things by our power and our privilege. We don’t think about race every day because we don’t have to, but our brothers and sisters don’t have a choice. They understand race and racism in a way that I never can, because for them it is a lived experience, a daily struggle.

If we hope to overcome our racism and find peace and justice in cities like Ferguson, then White people must begin by confessing. We are racist. I am racist. Racism is real.

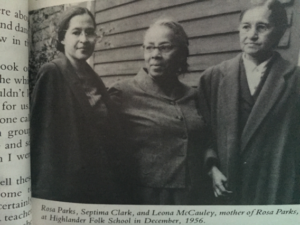

In the civil rights movement, people like Martin Luther King, Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, Septima Clark and many more brave, unnamed souls stood up against the racist laws and treatment they received in the South. They stood together, but they were in one sense alone. They stood up without the support of their White brothers and sisters, without those who held the seats of power. They stood on their own to demand their rights and demand justice. However, it wasn’t until White people stood in solidarity with African-Americans that the nation took notice. The images of firehoses and dogs being turned on peaceful protestors galvanized White Americans to go to the South and stand with their brothers and sisters for their rights and for justice. Then when a White minister from the north was killed there was a national outcry that helped pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It’s not right that the death of one White man mattered more than all the deaths of Black people that came before it, but it was a reality of life in those times that the solidarity of White people with the civil rights movement helped changes to the system come about more quickly.

The hashtag and slogan #blacklivesmatter that has emerged from the experience and protests in Ferguson and elsewhere reflects the fact that the reality of life during the civil rights era continues today. We have come so far and yet still have so far to go. I do think passing laws and regulations for police officers related to racial profiling, excessive force and other issues can have a huge impact on the treatment of people of color. It is an important step, like the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act. Yet no law or regulation will remove racism and prejudice from the hearts of human beings.

This is why the movement needs the confession of White people willing to stand with African-Americans and acknowledge our own complicity in the racism and systems that continue the legacies of slavery, colonization and White oppression. Without that solidarity those in power will continue to enforce the status quo and ignore the destructiveness of the systems that perpetuate racism. The hashtag reminds us that we White people must confess that White lives still matter more than Black lives.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying that the Black community needs a White savior to ride in and solve its problems. That “White savior” complex has caused more harm than good since the Voting Rights Act was passed. As people of privilege and power from the dominant culture, we White people must be careful that our solidarity and activism begins with confession and a lot of listening. When we speak truth to power it must come from an intimate understanding and relationship with those who face the struggle against racism and oppression every day. So please stand with our brothers and sisters of color by admitting and confessing that we are racist, that we don’t know or understand our own racism and that we need our brothers and sisters of color to teach us and lead us forward if we hope to find any peace and justice.

Lucas Land is an eco-theologian, urban farmer, writer and activist. He is avoiding growing up by constantly learning and trying new things. He is currently working toward a certificate in permaculture design. He was Urban Gardening Intern at World Hunger Relief, Inc. He worked on water and agriculture issues in Bolivia with Mennonite Central Committee. He also founded the sustainable landscaping business Edible Lawns here in Waco. He lives with his wife, three children and flock of chickens in the Sanger Heights Neighborhood in North Waco.

Lucas Land is an eco-theologian, urban farmer, writer and activist. He is avoiding growing up by constantly learning and trying new things. He is currently working toward a certificate in permaculture design. He was Urban Gardening Intern at World Hunger Relief, Inc. He worked on water and agriculture issues in Bolivia with Mennonite Central Committee. He also founded the sustainable landscaping business Edible Lawns here in Waco. He lives with his wife, three children and flock of chickens in the Sanger Heights Neighborhood in North Waco.

This article was originally published on Lucas’ blog, What Would Jesus Eat?, http://www.lucasmland.com/2014/12/01/solidarity-with-ferguson-i-am-racist/

(This post is one in a series on race titled “But Some of Us Are Brave.” The series includes posts from a diverse group of writers from our community. It takes a considerable amount of transparency and vulnerability for the contributors to this series to pen these posts and voice their experiences. We appreciate their courage, and we hope their willingness to be brave will spark some authentic community conversation on this sensitive and important topic. We hope you will read these posts thoughtfully and join the conversation by responding honestly and respectfully, and by sharing them with your friends and acquaintances. — ABT )

By DeShauna Hollie

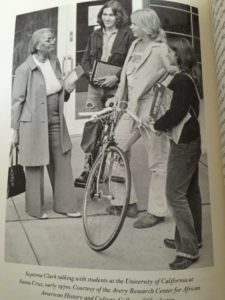

As I sat down to write about this theme of “But Some of Us Are Brave”, I thought of my favorite “super hero” Septima Poinsette Clark. Septima lived from 1898 to 1987. She was born in Charleston, South Carolina and lived much of her life there. Although Septima lived until she was 89, and is considered by many as the grandmother of the civil rights movement, her story isn’t as widely known as those of other civil rights leaders.

As a teacher and avid civil rights activist, Septima helped pioneer some important aspects of the civil rights movement. She helped to create Citizenship Schools that addressed the barriers and unjust laws that African Americans faced when it came to registering to vote in the South. These laws varied by county and state, but many required African-American voters to be able to pass a literacy test in order to vote unless their grandfather had voted in a previous election. This disqualified most Blacks in the South, because their grandfathers had been slaves and barred from voting. Activists like Septima found ways to address these laws while at the same time protesting them.

Septima also worked with Myles Horton of the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, TN to train other civil rights leaders and activists in non-violent civil disobedience. Rosa Parks attended one of those trainings and gatherings. Rosa went on to help lead the Montgomery bus boycott a few months later.

Septima used her training and passion as an educator to fight against systemic racism in the South. She consistently spoke up for the rights of marginalized people and continued to speak out even when her life was threatened, even when she was fired from her job as teacher for being a member of the NAACP, even when she was thrown in jail for holding integrated meetings with Whites and Blacks, and even when she was ostracized by many members in her community for using her voice to help others. She is indeed a super hero. In her later years, when asked about her work and contribution to the civil rights movement, she replied, “I don’t expect to see a utopia. No, I think there will always be something that you’re going to work on always. That’s why when we have chaos and people say, ‘I’m scared. I’m scared. I’m concerned,’ I say, ‘Out of that will come something good.’ It will too. They can be afraid of what is going to happen. Things will happen and things will change. The only thing that is really worthwhile is change. It’s coming.” (Clark, pg126)

Septima chose to continue working towards change her entire life, despite the consequences. Another quote of hers that I love goes: “It’s not that you grow old, but it is how you have grown old. I feel that I have grown old with dreams that I want to come true, and that I have grown old believing there is always a beautiful lining to that cloud that overshadows things. I have great belief in the fact that whenever there is chaos, it creates wonderful thinking. I consider chaos a gift, and this has come during my old age.” (Clark pg124)

Septima Clark is an inspiration to me and what I want my life to be like. I want to work for what I believe in my entire life. I want to work towards a more accepting society, a society that acknowledges that we are not a utopia. We have come pretty far since the days of slavery and segregation but the journey continues.

There is an elephant in the room that we are so afraid to mention. We are afraid and concerned that we may say something offensive, that we may hurt each other. The protests sparked by the shooting of Michael Brown on August 9th in Ferguson, MO, prompted questions in my mind about what I could do to stand in solidarity with that community and with others in my own community of Waco, TX, as we all grieved over the loss of a life. I’m not sure why this particular event spoke to me in a way that other shootings had not, but it made me want to take to the streets and scream “Black Lives Matter” and “Enough is Enough” along with other protesters. I love a good protest. They are invigorating and a great way to let off steam so that I can get down to the business of figuring out how to bring about the change that I am screaming about. Septima’s model of continual work and non-violence remind me that there is always a positive way to go about change.

The anger is real. The despair is real. The hurt is real. I believe it is time we made the conversation real. Although we are not Ferguson, MO,and are in Waco, TX, we have our own history of racism, prejudice and discrimination that is very real. I want Waco to prosper and I want to continue to work towards positive change in Waco. Will you join me in the conversation?

I know that conversations about change, about injustice, about past hurts and about how we move forward can sometimes be scary and hard. But dialogue with each other is the first action that we can take in being allies to each other.

This Act Locally Waco blog post was written by DeShauna Hollie. Deshauna grew up in Waco and is infant/toddler teacher at The Talitha Koum Institute Therapeutic Nursery. The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email [email protected] for more information.

This Act Locally Waco blog post was written by DeShauna Hollie. Deshauna grew up in Waco and is infant/toddler teacher at The Talitha Koum Institute Therapeutic Nursery. The Act Locally Waco blog publishes posts with a connection to these aspirations for Waco. If you are interested in writing for the Act Locally Waco Blog, please email [email protected] for more information.

Resources:

Charon, Katherine Mellen. Freedom’s Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel 2009.

Clark, Septima Poinsette and Cynthia Stokes Brown. Ready from Within: Septima Clark and the Civil Rights Movement. Wild Trees Press, Navarro, California:1986.